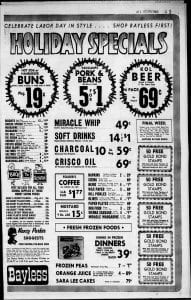

The Arizona Republic – September 3, 1965. Advertisement for Bayless grocery store Labor Day specials.

By Lora Key, Ph.D. and Shannon Fleischman

Americans celebrate the last three-day weekend of the summer with barbecues, pool parties, and shopping. Labor Day is an American tradition, but where did Labor Day come from?

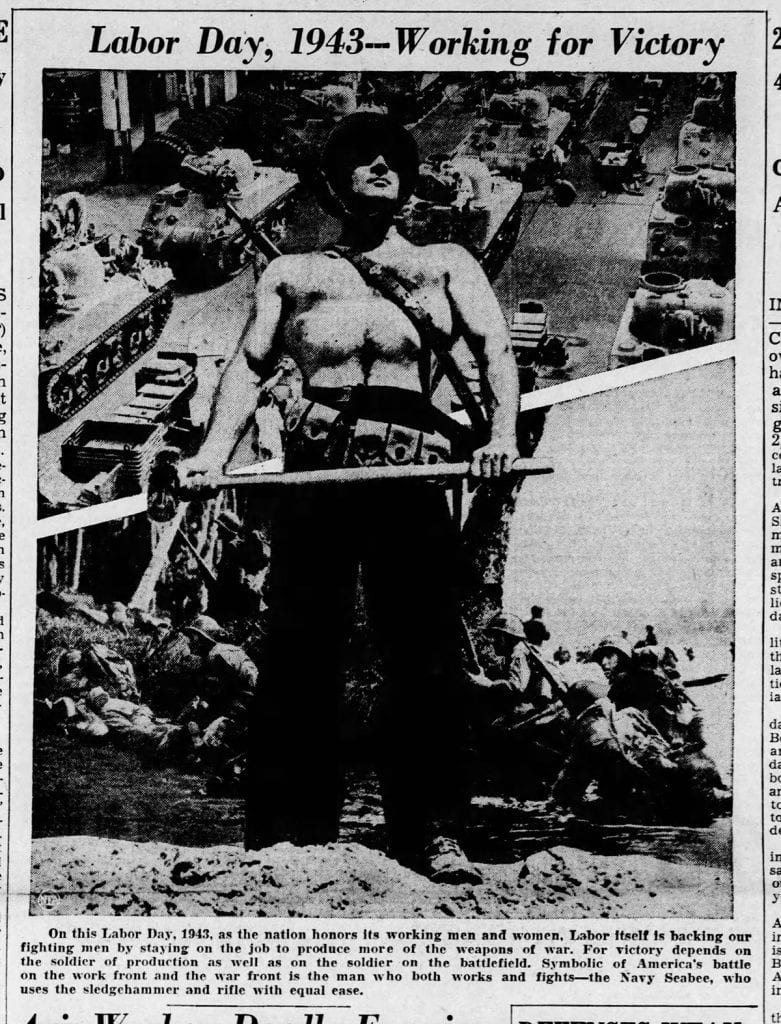

A Short History of Labor Day

Who were the essential workers of the past? In the late 1880s, essential workers (factory, mining, railroads, meat packing industries) faced low wages, dangerous working conditions, and 12-16 hour work days. One of the key aspects of acknowledging laborers with Labor Day celebrations was to limit work days to 10 hours and work weeks to 6 days a week. In the 1880s, labor unions across the United States began organizing celebrations of labor’s achievements and proposing a national holiday. Across Europe, May 1st (May Day) was International Workers’ Day, but for many Americans, May Day represented anarchists, socialists, and communists. Therefore, Americans adopted the first Monday in September as Labor Day. The first was celebrated in September 1882 in New York City and in 1884, President Grover Cleveland made it a national holiday. So as you celebrate the long weekend, remember that labor unions and workers made it possible. At the heart of labor unions is the power of advocacy to make changes in a community.

Labor in Arizona

Arizona is not typically thought of as a place of labor activism or where labor unions flourish. However, there have been active laborers and workers organizing for workers rights for longer than Arizona has been a state. This blog post will briefly review some of the more prominent labor strikes and labor legislation in State’s history. The first major strike took place in 1884 at Tombstone. The mine owners lowered the daily wage from $4/day to $3/day (a reduction of 25% of wages). Over 300 workers participated in the strike which lasted four months. The strike ended when Federal troops were sent from Fort Huachuca and gave workers the option: either accept the lower wages or find a new place to work.

In Globe, AZ in 1896, the Old Dominion mine attempted to lower the wages of white miners to those of non-whites from $3/day to $2.25/day. White miners threatened the mine owners at gunpoint over the loss of wages and eventually joined the Western Federation of Miners Union. The mine owners locked the mine and the Territorial Governor issued marshal law to gain control over the striking workers. The collective power of the workers eventually forced the mine owners to reinstate the white miners wages to $3/day.

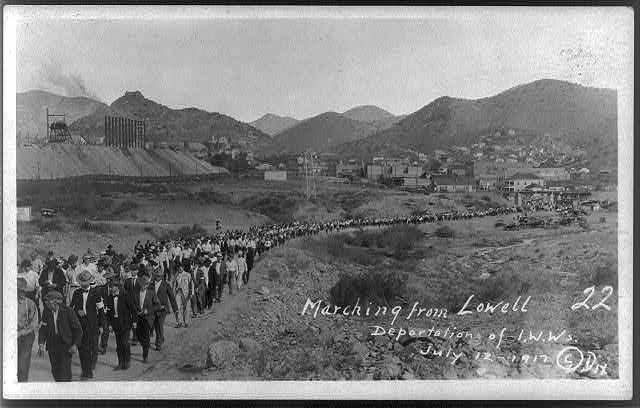

During World War I, copper was an integral part of the war effort. With this demand, copper mines in Arizona attracted workers from across the country with steady wages and jobs. Workers from The Industrial Works of the World (IWW or Wobblies) came to the State for these jobs. In 1917 the IWW organized 5,000 workers to go on strike in Jerome, Bisbee, Mayer, and other towns with copper mines across the State. This strike resulted in the Bisbee Deportation, arguably the most known event in Arizona labor history. The mine owners in Bisbee worked with local law enforcement and had IWW workers and anyone they thought might be sympathetic to IWW cause, over 1,200 people in total, deported to New Mexico.

Photo: Bisbee Deportation, marching from Lowell July 12, 1917 (Credit Library of Congress)

In 1946 the Arizona State Legislature passed Right to Work legislation, which went into effect in 1947. Right to Work legislation essentially states that employees are not required to join a union in order to be hired or not be fired from a job. In practice, Right to Work legislation is meant to weaken the power of unions and their collective bargaining.

Women on the picket line. Photo by Mari Schaefer, 1983. Courtesy of Ricky Wiley, Arizona Daily Star. Source: On the Great Arizona Copper Strike 1983-1986

The last real stand for labor unions in Arizona came in 1983 in Clifton. The labor dispute was between Phelps Dodge Corporation and union copper workers and mill workers organized by the Steel Workers Union. The strike was a result of falling copper prices and the mine owners cutting wages based on the decline in price. The strike was contentious, lasting over three years. Phelps Dodge eventually replaced the majority of striking workers with non-union employees, which led to these workers (or scabs as they are often called), voting to decertify the unions. The result was over 35 local union chapters being decertified in Arizona (as well as New Mexico and Texas where Phelps Dodge operated). This is generally considered to be the largest blow to organized labor in modern U.S. history.

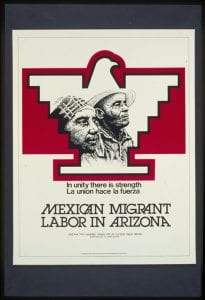

Labor unions and organizations have continued to exist in Arizona, but labor members are not in the majority of workers. This is partly due to the history of labor activism highlighted above, the low density of population, and because of the industries in Arizona. However, labor unions are still active in Arizona, and workers continue to organize via collective bargaining, one example is in the poster.

Rosa McKay by Laurie McKenna

Rosa McKay’s Story

Rosa McKay was born in Colorado but moved to Arizona in 1904. Rosa was elected to be a state legislator in 1917 and represented Cochise County. In July of that year she became outraged by the Bisbee deportation and fought for the 1200 striking miners and their supporters.

Because of her strident support for labor, she was run out of the county with threats against her life by the pro-company anti-union loyalty league of Bisbee. This did not deter her from serving the people and she represented Gila County from 1919 to 1923. During her time in the legislature she secured passage of a minimum wage act for women. House Bill 3 was signed into law by Governor Thomas E. Campbell on March 8, 1917. Rosa died in 1934,at the age of 53 . The state flag was lowered to half mast in her honor.

Drawing courtesy Laurie McKenna from her 2017 project “The Undesirables”

Read more about Rosa McKay on the State Library’s website.

Learn more about Arizona’s Labor History with the Journal of Arizona History

Jack Reid, “The ‘Great Migration’ in Northern Arizona”

Daniel Arreola, Drew Lucio, and Christopher Lukinbeal, “Mexican Litchfield Park”

Robert J. Moore, “Hard Work and Good Times at Chevalon Canyon”