On June 19, 1865, Union soldiers arrived in Galveston, Texas, bringing word that the war had ended and the enslaved people of the Gulf Coast island were free. Celebrations of June 19th – known early on as “Emancipation Day” or “Jubilee Day,” and later, “Juneteenth” – began in Texas soon after, spreading to other communities throughout the country as African American families migrated to other cities. This year – the first since Juneteenth was named a federal holiday – large-scale celebrations are planned throughout the country, including Tucson, where an official Juneteenth festival has been held since the early 1970s. But local recognition of the holiday actually began much earlier, with references to the celebration appearing in major Tucson newspapers in the early 20th century.

Arizona Daily Star, June 14, 1904

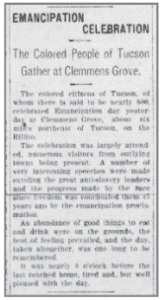

The majority of African Americans who made their way to Arizona in the early 20th century came from Texas, and they brought with them this annual celebration of Black liberation. Juneteenth celebrations in Tucson began as informal gatherings hosted at local homes and outdoor picnic spots. In the early 1900s, folks from Tucson as well as delegations from Phoenix, Bisbee, Douglas, and other small towns traveled to Tucson for an annual celebration held at Clemmons Grove, the location of which is listed as “about six miles northeast of Tucson, along the Rillito River.” (Arizona Daily Star, June 20, 1908).

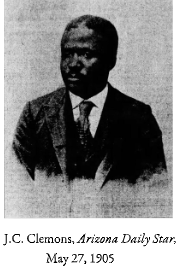

Though I’ve been unable to pinpoint this exact location, it’s likely that it was hosted by the Clemmons family, headed by J.C. “Boss” Clemmons and his wife, Anna, who migrated to Tucson from Burleson, Texas around that time. J.C. became a leader in the Black community, serving as president of the “Civil Rights Club,” advocating for labor rights, and rallying Black voters to weigh in on pressing issues like Arizona statehood.

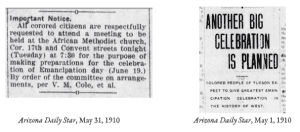

Between 1900 and 1910, the African American population of Tucson grew from 88 to 220 and with it the Juneteenth festivities grew. Committees met at local churches to plan for the celebration, by then hosted at the popular Elysian Grove park in downtown Tucson. As larger delegations from other Arizona cities flocked to Tucson as the epicenter of the festivities, well-known speakers and politicians from Texas were invited by organizers to attend what Clemons heralded as the “Greatest Emancipation Celebration in the History of the West.” “You will always find the colored men of Pima county right in line in the front ranks of progress and enterprise,” Clemons stated in anticipation of the 1910 event; “We are adding our share to the advertising of the city and to its general prosperity by keeping in the front ranks of progress.” (Arizona Daily Star, May 1, 1910).

In subsequent years, the Elks Club and other social clubs hosted and planned gatherings, but the combination of the Great Depression, world wars, and Jim Crow segregation led to a nationwide decline in celebrations of the holiday in the mid-20th century. By 1970, residents of the A Mountain neighborhood saw a need for a renewed Juneteenth celebration in Tucson. Morris Doty, Bobby Ray Dixon, and Robert “Baby Owl” Foley got together to plan a day of entertainment and celebration for the community, a tradition that continues to this day. After outgrowing its original location, the Tucson Juneteenth festival is now held at Kennedy Park and is attended by thousands of people each year. This year marks the 51st year of the festival and a return to an in-person event festival after the Covid-19 pandemic disrupted plans for a large 50th anniversary celebration.

Tucson Juneteenth Festival Facebook (@tucsonjuneteenthfestival)

It wasn’t until 2016 that Arizona became the 45th state to recognize Juneteenth as a federal holiday – and it was only recently made a federal holiday by President Biden in 2021 – but formal celebrations of June 19th in the Old Pueblo have been held for nearly 120 years, commemorating the ongoing movement for representation and cultural celebration of Black Arizonans.

Sources

Arizona Daily Star

Lawson, Henry. The History of African Americans in Tucson: An Afrocentric Perspective, 1997.

Perri Pyle, Archivist