Starting A Conversation Sometime between closing on November 4th and opening on November 5th, the two statues―honoring John Greenway and Padre Eusebio Kino―in front of the Arizona History Museum in Tucson were painted with red spray paint. As a history institution, we paused to reflect on what this means.

Sometime between closing on November 4th and opening on November 5th, the two statues―honoring John Greenway and Padre Eusebio Kino―in front of the Arizona History Museum in Tucson were painted with red spray paint. As a history institution, we paused to reflect on what this means.

First, we have to ask questions about memorializing people from the past in statue form. What purpose do monuments, memorials, and statues serve? Statues and monuments are important to communities as a way to celebrate, grieve, or remember the past. Around the globe, people and institutions are reevaluating the monuments around them, determining if their values are still the same as they were in the past. Communities must ask themselves if monuments are dedicated to people who do not represent the community, what is to be done with the physical monuments themselves? When institutions are slow to make a determination, community members sometimes take matters into their own hands.

Placing These Statues in Context

The Statue of John Greenway

In the early twentieth century, John Greenway was one of the most powerful men in Arizona. He worked for some of Arizona’s largest mining companies and helped to establish the town of Ajo, Arizona. Mining revolutionized Arizona’s economy and led to a population boom. But Greenway also represents one of the most difficult moments in Arizona history: as General Manager of Calumet & Arizona Copper Company, he helped organize the infamous Bisbee Deportation in 1917. Greenway’s role in the Bisbee Deportation marred his reputation, led to an indictment, and derailed his budding political career.

Isabella Greenway, his wife and Arizona’s first female representative in Congress fought to preserve her husband’s legacy by campaigning to have his statue added to National Statuary Hall in Washington, D.C. The statue of John Greenway was cast by Gutzon Borglum, the same artist who sculpted the faces on Mount Rushmore. It was dedicated in 1930. In 1974, Greenway’s son, Jack, donated $50,000 to the Arizona Historical Society in order to erect a memorial to his father―a second casting of the Borglum statue was made and placed in front of the Arizona History Museum in Tucson.

The Statue of Father Kino

Eusebio Chini, also known as Padre Eusebio Francisco Kino (Father Kino), arrived in the Pimeria Alta, what is now southern Arizona and Sonora, Mexico, in 1687. Kino is known for introducing crops like citrus, pomegranate, and winter wheat to the Sonoran Desert. When Kino introduced these European crops, it destabilized important and culturally significant Indigenous food systems and encouraged dependence on the Missions. Kino was reported to be genuine and warm toward Native American peoples, but this evidence comes from Kino himself and fellow Spanish missionaries, not Native people. Although Kino died in 1711, communities in the American Southwest and Mexican Northwest still grapple with the painful realities of colonialism. Statues of missionaries, conquistadors, and settlers are constant reminders of this difficult history.

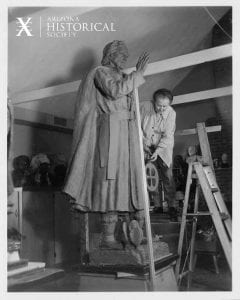

The Kino statue was sculpted in 1965 by Suzanne Silvercruys, a Yale-educated Belgian immigrant and anti-communist activist. Kino was selected to represent Arizona in Statuary Hall for his religious, scientific, and civic contributions to the state’s history. Selecting Kino for the National Statuary Hall was a bipartisan effort, garnering support from both of Arizona’s U.S. senators, Carl Hayden (Democrat) and Barry Goldwater (Republican). In the 1960s, the admiration of Kino was popular among Arizona’s businessmen, who saw themselves as the successors of Kino by turning “nothing” into “something” through mining, agriculture, military technology, and electronics. The Arizona Historical Society likewise spearheaded several efforts to memorialize Kino from the 1950s to the 1990s. The copy of the Kino statue has been in place in front of the Arizona History Museum since the 1970s.

History Happens Every Day

The most important lesson history can teach us is that the past is not written in stone–or, in this case, cast in bronze. It lives, it breathes, and each generation adds a new layer of interpretation. These layers of interpretation can, and usually are, in conflict with each other. Historians strive to see both realities at the same time, understanding that everyone has a different perspective on the past. We invite you to think about what stories statues tell and what stories they don’t.

The tagging, toppling, and defacement of statues in Arizona and the United States has sparked a long-overdue conversation about whom institutions memorialize and why. We hope that by providing a fuller picture of Arizona’s history and the historical figures whom people in the past have chosen to honor, you will have a better understanding of the present debate.

Continuing the Conversation

In September of 2020, AHS partnered with the ASU School of Historical, Philosophical and Religious Studies for a virtual program, AZ History Now: Monuments and Memorials, which discussed a number of memorials and monuments across the state. The John Greenway statue was one of the statues talked about in the program. This blog post and this program are just the beginning of how AHS will continue to engage on this topic of who is memorialized and why through public programming, interpretation, and The Journal of Arizona History.