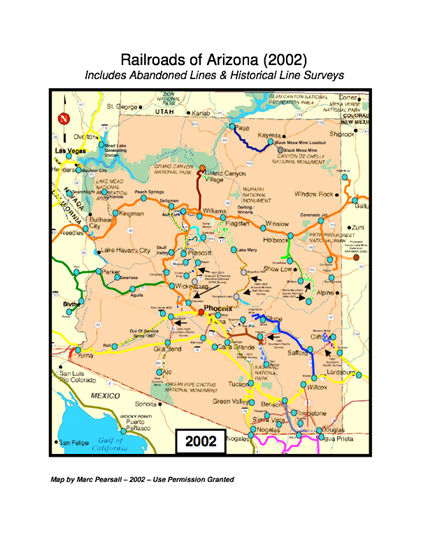

Traveling through Arizona during Esperanza’s time was done many different ways, from horses, to stagecoaches, to trains. People loved to move around, see sights, and connect to the world outside of Tucson. When a mail route came to Tucson, people were able to write and receive letters from friends and family around the country. The railroad coming to Tucson meant more goods, people, and opportunities in Arizona.

Chapter 5, Page 35, “Senor Mansfeld spoke in a thick German accent. He poked Senor Levin’s vest with one stiff finger to emphasize the point he was making. He said, “My friend, we aspire to make this a civilized town. And I say we are getting there. We have a telegraph, law and order, my bookstore of course, and now I hear Southern Pacific builds a railroad to connect us with California and Texas. All good steps towards modernization.”

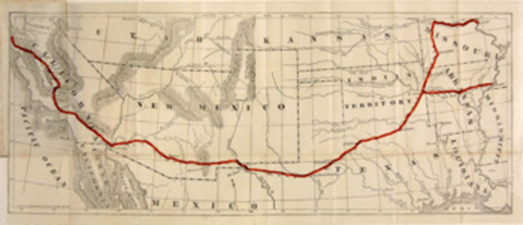

The Butterfield Overland Mail Trail, also known as the Oxbow Route, the Butterfield Overland Stage, or the Butterfield Stage, was a stagecoach route in the United States, operating from 1857 to 1861. It was a United States mail delivery service that began in two cities – Memphis, Tennessee and (Tipton) St. Louis, Missouri. The mail routes converged at Fort Smith, Arkansas and continued through Indian Territory, New Mexico, and southern Arizona to its final destination in San Francisco, California. (See map above.) The service provided communication between the eastern United States and the western states and territories before coast-to-coast railroad service began. The cost of mailing a letter was 10 cents.

The trip, about 2,800 miles, was made in twenty-five days and sometimes less. Lack of water and possible hostile attacks constantly troubled the route.

Though the coaches had the mail as their first priority they also accepted adventurous passengers at a cost of $150 – $200. Passengers were allowed 25 – 40 pounds of luggage, two blankets and a canteen. The coaches traveled at very fast speeds twenty-four hours a day; there were no stops for bed and breakfast – only the hurried intervals at the station houses when they changed horses or mules – at all hours of the day and night.

As they approached the stations, they would blow a brass horn to let the station keepers know they were near and to get ready. Up to ten men worked at the stations to help with the exchanges.

At some of these stops, travelers were offered meals of bread, coffee, meat and, sometimes, beans, costing passengers an extra $25. Coaches passed through southeast Arizona twice a week on Sundays and Wednesdays – from both California and Missouri.

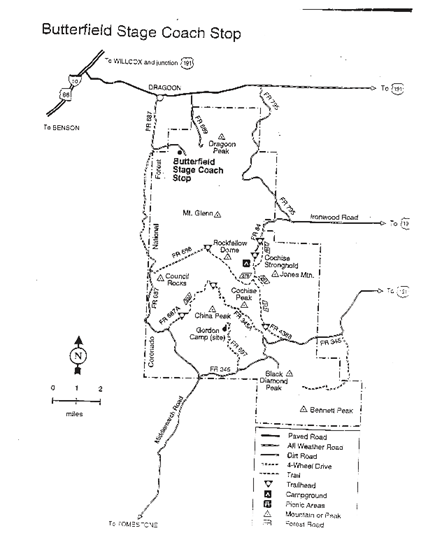

The route through southeastern Arizona from 1858 to 1861 crossed into what is now Arizona from Mesilla, New Mexico Territory at Stein’s Pass, and then headed west/southwest to San Simon, through Apache Pass, Ewell Springs, and Dragoon Springs (about twenty miles north of Tombstone). It crossed the San Pedro River just north of present-day Benson and then veered slightly north to pass Cienega and head up to Tucson and on to San Francisco via Yuma and Los Angeles. In Arizona, the most dangerous station stop was at Apache Pass. It was situated there because of the availability of fresh water at Apache Spring.

The outbreak of the Civil War caused the quick withdrawal of almost all military troops from the frontier territory, leaving the area unprotected. In February 1861, when Texans voted to secede from the Union, the southern mail route was discontinued in favor of a northern route.

In fact, during the Civil War, Arizona Territory was cut off from much communication with the outside world. The next public mail to reach Tucson came from California on horseback on September 1, 1865. Regular mail delivery wasn’t restored until the 1870s and 1880s.

Although the Butterfield Overland Stage mail and passenger delivery lasted only 2 1/2 years, it opened up the West to further settlement and introduced the country to its newest territories.

The Celerity or mud stagecoach (see above) carried mail, newspapers, small packages and passengers through the rougher, more mountainous western leg of the trip. It was lighter in weight, faster, could carry luggage on top, and had a canvas roof and curtains. (Though the curtains weren’t able to keep the wind, dust and rain off of passengers.)

It was one-half the cost of the deluxe Concord coach used on the earlier leg of the route. The red and yellow-trimmed mud coaches carried 9 passengers and its three seats could be folded into a small bed. A team of horses or mules – the number depended on weather and weight – pulled the Celerity. The name, Celerity, came from the Latin root, celer, meaning “swift.”

The stagecoaches traveled at an average speed of 4 – 7 miles per hour covering anywhere from 70 to 120 miles each day. It made stops at 139 relay stations or frontier forts, located every 20 miles, on the journey. They would load and unload the mail and passengers, eat, get fresh water and new horses. Butterfield employed over 800 people to drive the mail and passengers across the country.

The Butterfield Stage was only attacked once by Apaches, but also could be stopped by highway thieves or outlaws; due to this possibility, Butterfield did not allow gold or silver to be transported on his stagecoaches.

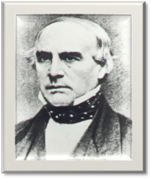

In 1858 John Butterfield of Utica, N.Y. won a government contract of $600,000 a year for six years to carry mail from St Louis to San Francisco twice a week. Butterfield had much experience in the staging business. Born in New York in 1801, he had received little formal education; he had gone into staging, becoming a driver while still in his teens. Through hard work and ability he had risen to ownership of several stagecoach lines in New York. By 1857 he was a prominent businessman and personal friend of the president.

Butterfield, after signing the contract, began working non-stop to ready the service to begin in 1858. His first necessity was hiring experienced frontiersmen and drivers seeking men friendly with the various Indian tribes that would be encountered along the route. Beyond hiring employees, creating the route, and constructing the way stations, Butterfield also had to purchase the horses, mules and stock for his line. He hired superintendents to manage the stations and conductors to sit beside the drivers; conductors were in charge of the coaches; drivers handled the coaches. Each driver had to know his 60-mile stretch of road extremely well because of night travel.

Butterfield famously told his drivers, “Remember boys, nothing on God’s earth must stop the mail!”

~A newspaper reporter, Waterman Ormsby, was the only passenger on the first East-West run of the Butterfield Stage who journeyed the entire distance of the mail route. He sent reports to the New York Harold newspaper describing his journey; he later wrote a book about his experiences on the trip.

Start of the journey:

Our horses were four in number, that being the allotment all along the line from St. Louis to San Francisco. They were harnessed at this point and to change teams was the work of but a few minutes, and we were off again. This time we got a driver who was slow . . . [and] did not know the road well, and we had to feel our way along. As the night was dark, the roads difficult, and the coach lamps seemed to be of little use in the dim moonlight . . . I began to feel some fear of wet feet and mail bags when the water reached the hub, but we got over safely and pretty dry, as the water was not deeper than half of the wheel. . . I must confess it was a matter of utmost astonishment to me how the driver ever found his way in the wilderness.

Food:

[We had…] jerked beef (cooked on the [buffalo] ‘chips’), raw onions, crackers slightly wormy, and a bit of bacon.

Desert Flora and Fauna:

As we travelled leisurely through the desert, we were refreshed with a decidedly cool and delicious breeze, while the atmosphere was by no means so unpleasant to me as in New York in a hot August day, though we were then about half way between the thirtieth and thirty-second parallels of latitude. There seemed to be an abundance of animal life on the desert. We saw large droves of antelopes frequently, and numbers of quail, snipe, and other specimens of the feathered tribe, while the “dog towns,” or holes, of the prairie dogs were innumerable. This animal seems to be a cross between a squirrel and a rat terrier, and lives in holes that it digs in the ground. As we approached their towns we could see their shaking tails as they rushed frightened to their homes. They live on grass and weeds, and never trouble anybody except by undermining the road with their [underground] borings.

Crossing the Pecos River:

As I lay dozing on the seat, about three o’clock on Sunday morning, I heard a cry from Jones that we had reached the Pecos River, and there we were, true enough, right into it. After hallooing and blowing our horn, we obtained an answer, as we supposed, from the other side of the river, telling us to drive up stream, which advice we followed, when to our astonishment we found ourselves in camp on the same side of the river. The fact is the Pecos makes such a turn here that you can hardly tell which side you are on. It is a swift stream, with a good body of water, rising away up in the Rocky Mountains and emptying into the Rio Grande. It is much the color of the Mississippi. There were no trees or any unusual…foliage on the banks at the point where we struck it; so that if our driver had not been on the lookout we might have been wallowing in its muddy depth.

~James Henry Tevis was an adventurous young man who found employment with the Butterfield Overland Mail Company, first helping to build the Apache Pass station, and then staying on as the station agent. He described the Apache Pass station:

A stone corral was built with portholes in every stall. Inside, on the southwest corner, were built, in L shape, the kitchen and sleeping rooms. At the west end, on the inside of the corral, space about ten feet wide was apportioned for grain room and storeroom, and here were kept the firearms and ammunition.

~William Tallack rode from San Francisco to St. Louis on the Butterfield Overland Mail Company stages June and July, 1860. The Englishman was returning to England from Australia by way of the United States. He shared some of his observations of traveling on this trail.

Stagecoach Comfort:

[I] often felt doubtful as to how far [I] might be able to endure a continuous ride of five hundred and forty hours, with no other intermission than a stoppage of about forty minutes twice a day, and a walk, from time to time, over the more difficult ground, or up and down stiff hills and mountain passes, and with only such {sleep] at night as could be obtained whilst in a sitting posture and closely wedged in by fellow-travelers and tightly filled mailbags.

Changing Stagecoaches:

It being one o’clock in the morning, and a dark night, we had to be very careful that none of our respective packages or blankets were left behind in the hurried operation of changing; so we tumbled hastily into our new wagon, wrapping ourselves up in coats or blankets nearly as they came to hand, waiting till morning for more light and leisure to see which was our own. By means of a blanket each, in addition to an overcoat, we managed to settle down warmly and closely together for a jolting but sound slumber.

Food:

Meals (at extra charge) are provided for the passengers twice a day. The fare, though rough, is better than could be expected so far from civilized districts, and consists of bread, tea, and fried steaks of bacon, venison, antelope, or mule flesh—the latter tough enough.

On the scenery:

The Apache Pass was a rugged, but very picturesque portion of our route and will be long remembered…as the scene of the finest storm and sunset…ever witnessed.

~Raphael Pumpelly was a noted American geologist who rode on Overland Mail Company stages west to Tucson.

On the stagecoach:

The coach was fitted with three seats, occupied by nine passengers. As the occupants of the front and middle seats faced each other, it was necessary for these six people to interlock their knees; and there being room inside for only ten of the twelve legs, each side of the coach was graced by a foot, now dangling near the wheel, now trying in vain to find a place of support. An unusually heavy mail in the boot, by weighing down the rear, kept those of us who were on the front seat constantly bent forward. The fatigue of uninterrupted traveling by day and night in a crowded coach, and in the most uncomfortable positions, was beginning to tell seriously upon all the passengers, and was producing in me a condition bordering on insanity.

Accounts adapted from The Over-Land.

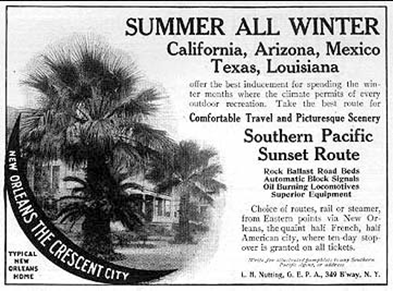

Review the advertisement to sale tickets on the Southern Pacific Railroad Line’s Sunset Route through Arizona. Does it sound like today’s tourism ads?

A whistle-stop on the Southern Pacific Railroad route, the Willcox, Arizona’s (passenger) Depot Station, is the only original Southern Pacific building left in Arizona; today it is the Willcox Town Hall.

| Research the Concord Stagecoaches that cost $1300 each. Compare the Concord with the Celerity mud model. Send a postcard to a friend describing your journey on a Concord coach; include a description of the coach. | Read the information about the Butterfield Stage and other travel and then write a paragraph summary of what you learned. Post your summary in the classroom. |

Choose 2 different primary source accounts of traveling on the Butterfield Stage. Compare their travel experiences in a graphic organizer. Would you have paid $200 to ride the stagecoach? Why or why not? |

| Research the Hashknife Pony Express; the group started in the 1950s in Arizona to honor the 1860s Pony Express and it continues today. Click to View Video about the Pony Express. A good site to research this topic is Wikipedia. | Mr. Butterfield told his drivers, “Remember boys, nothing on God’s earth must stop the mail!” Write a list of the top tenpossible events that could possibly stop the mail. |

In the story, Esperanza Means Hope, at Señor Ochoa’s party, the men talk about the Southern Pacific Railroad and its importance to Arizona. Research this railroad line and share your learning in an online blog. |