On June 19, 1865 Union soldiers, led by Major General Gordon Granger, arrived in Galveston, Texas and brought word that the Civil War had ended and enslaved persons were free. The newly freed men and women celebrated, left the plantations, and sought their long-lost family members. Juneteenth, the name derived from the month and date, became a local celebration in 1866. But soon, Juneteenth celebrations spread across the country and stretched across generations.

But there is some confusion about the origins of Juneteenth. While school children learn that the Emancipation Proclamation freed the enslaved on January 1, 1863, in reality, the Proclamation had little effect on actually freeing the enslaved peoples. It only freed enslaved people in Confederate-controlled areas of the South. On the ground, freedom often depended on the presence of Union troops. Without Union troops to enforce the Proclamation, life continued as it was for the enslaved since most southern slaveowners ignored President Lincoln’s Proclamation. As Union troops advanced across the South, enslaved persons left the fields and ran towards the troops and towards freedom. In Texas though, which remained semi-isolated with few Union troops, enslaved peoples had little chance to escape to Union lines, even after the Emancipation Proclamation. Until Major General Granger arrived with Union troops the enslaved in Texas could not be truly emancipated. Thus, when Major General Granger arrived in Galveston with news that the war ended and read General Order #3 (which superseded the Emancipation Proclamation), Juneteenth was born!

Juneteenth, Arizona Style

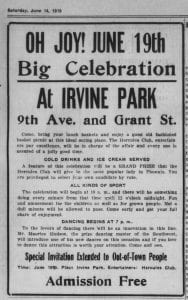

Juneteenth is uniquely Texan in its origins, but in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries some Black Texans left the Lone Star State for Arizona, bringing their traditions, including Juneteenth celebrations, with them. Histories of Juneteenth celebrations in Arizona are sorely lacking–museum archives and collections, until very recently, have tended to center official records or powerful figures, largely missing the stories of regular citizens, people of color, and women. Records suggest that one of the earliest public Juneteenth celebrations was in Phoenix in 1919. We cannot say for certain that there were no earlier celebrations in Phoenix or elsewhere in the state.

Due to both de jure (by law or legally recognized) and de facto (in effect, or resulting from social or cultural factors) segregation and discrimination it was difficult for Black community leaders to rent facilities or public spaces for Juneteenth festivities. As a result, many Juneteenth festivities were relatively small, organized by churches, neighborhood associations, or schools. Juneteeth celebrations became bigger and more public in the 1950s and 1960s when middle-class Black Arizonans used their social influence to fight for representation and respect. In Phoenix, for example, Helen Mason, the granddaughter of the first Black Phoenican Mary Green, and Eleanor Ragsdale, a prominent Black civil rights activist in Phoenix, both used their social influence to popularize Juneteenth among Black Phoenicians. While some cities like Tucson and Phoenix have had Juneteenth celebrations for almost 100 years, most major cities in Arizona have had public Juneteenth celebrations since at least the 1990s.

To read more about Juneteenth check out:

Tyina Steptoe, Houston Bound: Culture and Color in a Jim Crow City (Oakland: University of California Press, 2016).

Elizabeth Hayes Turner, “Juneteenth: Emancipation and Memory,” in Lone Star Pasts: Memory and History in Texas (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2006).