Fort Bowie

Army camps and forts were established in Arizona by the military and authorized by the U.S. government. They were built to house troops (or bluecoats as they were called by some) who would help maintain the peace on the frontier by enforcing Indian treaties, by keeping white settlers off of Indian lands and later, by providing protection to settlers when hostilities occurred.

Army posts were called camps when only a few troops were assigned to the particular location, or if it was only a temporary post. Once a greater number of troops were assigned to the location or it became a permanent post, it was then referred to as a fort.

All the forts were similar in that they all had barracks, stables, officers’ quarters, storehouses, hospitals and offices for the fort’s headquarters. Buildings were arranged around a central parade and/or drill grounds. Contrary to popular belief, most forts did not have walls surrounding them; direct attacks on forts were rare. However, all forts were strategically located and established near a source of water. Because soldiers’ families were allowed to live there, some forts also had schools.

Soldiers, themselves, built the forts out of materials that were found locally. If forests were nearby, then wood was used; in the deserts adobe buildings were constructed and in some locations, stone buildings were erected.

As forts continued to grow, over time, more facilities and buildings were added. Often, blacksmith shops, mess halls, and laundries, to name a few, were added to the forts. By the time, it was decommissioned, Fort Bowie, for instance, became somewhat luxurious. In addition to some 36 structures, flush toilets and street lamps, a tennis court and a steam-powered ice-making machine were installed at the fort.

A soldier’s life was difficult, lonely and often boring at these isolated, frontier army outposts. The vast majority of troops (privates) saw little or no combat and spent their days practicing drills, serving guard duty, preparing for inspections and working on manual labor projects – all for a monthly pay of $13.00. (Corporals made $15.00 per month and sergeants made $17.00 monthly.) Isolation often meant there were no nearby towns for the enlisted men to relieve the monotony of duty. In fact, the monotony of frontier troop life was too much for many of the soldiers and desertion rates were high – anywhere between 30%, as a high, to 19% of troopers deserted.

Army records show that the average age for an enlisted soldier was 23 years old and that the enlistment term was for five years. Many of the troopers were former Civil War soldiers and many were uneducated and illiterate. Training of soldiers was often sub-standard and sometimes troopers weren’t even able to ride horses (or mules) well enough to fight while on horseback.

Just as in the Civil War, high standards of hygiene were not initially enforced and therefore, diseases ran rampant. Far more troopers were treated for and killed by cholera, dysentery, malaria, fevers and other ailments rather than as a result of wounds received in combat.

Meals were generally considered poor and unappetizing – menus included hash, stew, baked beans, salt bacon, coffee, and bread. Sometimes, troops maintained vegetable gardens and hunted fresh game to supplement their meals. Brown sugar, molasses and vinegar were also stocked.

Camp Bowie was actually established in 1862 during the Civil War near the Apache Pass station of the Butterfield Overland Mail route. Both the station and the fort were situated at this location because of the natural springs that provided water for travelers and their animals. Apache Pass is tucked between the Chiricahua Mountains and the Dos Cabezas (two heads) Mountains. This area was also part of Apacheria. Lands of the southern four corners area (SE AZ, SW NM, NW Chihuahua, and NE Sonora) were home to four different Chiricahua Indian bands.

Fort Bowie became the center of Army operations against the different bands of Chiricahua Apaches and their famous leaders, Cochise and others. Fort Bowie troops played a key role in the pursuit of Geronimo, born into the Bedonkohe band of Chiricahua Apaches, who resisted giving up his homelands and being forced onto a reservation.

In fact, the Apache Wars between Americans and Apaches from 1851 – 1886 ended in the vicinity of Fort Bowie with the surrender of Geronimo for the final time.

Camp Lowell

Fort Lowell Museum

In the story, Esperanza Means Hope, Lt. McKinney, suitor of Mariá Elena, was based at Camp Lowell near Tucson. Camp Lowell was first established inside Tucson city limits. At that time, Tucson was a small, dusty town, with some interesting characters as residents – gamblers, rustlers and the like. Two problems for the commanding officer, Captain Brown: the lawlessness that prevailed in town and the poor health conditions. So, General Crook sent a party to find a new and improved location for the camp. The group picked a site 7 miles northeast of Tucson because of its availability of water, grasses for stock and its ample wood supply. Simple adobe buildings were constructed at first, but were improved upon as time passed. The camp was moved to the new location in March 1873 and renamed Fort Lowell. (The fort was named in honor of Brigadier General Charles Russell Lowell, Jr., 6th U.S. Cavalry, who was killed in Virginia during the Civil War.) Despite malaria and other afflictions that were still common in the region, the fort became a desirable post for officers with families.

There were all the standard accommodations at the fort, plus a few extras, including a camp garden, a rifle range, a parade ground lined with cottonwood trees, a cemetery, picket fences and sidewalks. Eventually the fort grew to over 30 adobe and wood structures to accommodate the average number of people living there – between 130 to 240 enlisted men and officers as well as their families.

There was even an organized baseball team that played against Tucson teams and old-fashioned picnics. However, the favorite activity for the people of Tucson, was listening to the Fort Lowell Army Band; the band entertained at concerts, parades, and dances, attracting many people from town.

A famous surgeon attached to Fort Lowell from 1876 -1877, Dr. Walter Reed, later discovered the cause of yellow fever and today has a major Army hospital in the Washington D.C. area named in his honor.

The troopers stationed at Fort Lowell escorted wagon trains through the area, protected settlers, patrolled the borders, guarded depot supplies and fought against Apaches.

With a visit to the Fort Lowell Museum located in Fort Lowell Park, nineteenth century frontier military life and its history can be explored by enjoying its permanent exhibits and displays. Although the fort was closed in 1891, after the conclusion of the Apache Wars, part of the original Army post remains. For example, the original hospital ruins are protected for viewing purposes. The original Officer’s Quarters and their kitchens have been reconstructed circa 1885. The museum was opened in 1963; a large bronze statue sits on the grounds.

On page 163 of Esperanza Means Hope, Carlos mentions the Camp Grant Massacre of Apaches while under the protection of 1st Lt. Royal Whitman, commander of Camp Grant. While many in Arizona, believed the killing of the 144 mostly sleeping women and children by 92 O’odham Indians, 48 Mexicans and 6 Americans near the Aravaipa Creek was justified, people back East and the President were horrified. President Grant ordered Governor Safford to bring the responsible men to trial. The five-day trial ended in a “not-guilty” judgment by the jurors. Several of Tucson’s leading civic and business leaders were involved in the planning and execution of the massacre. In 1996, a coalition of Tucson clergy and others, apologized to San Carlos Apaches for the massacre.

* On your own, research more information about the massacre.

The following is from Rick Leis, President, Coalition of Prayer Network International.

On October 5, 1996, approximately 80 people traveled from Tucson to the San Carlos Apache Reservation. Their purpose was to apologize to the San Carlos people for the Camp Grant Massacre. It took four years to set up the meeting. We met at the San Carlos Historical Museum. About 130 were present, including Chairman Stanley, Dale Miles (Tribal Historian), and David Miles from the San Carlos tribe. There were many tribal elders from the San Carlos, White River Apache, Navaho, Hopi and Desert Cahuilla (Chawilla) tribes.

People representing the groups, and families that were responsible for the massacre stood before the gathering, took responsibility for the slaughter and begged forgiveness. At the conclusion of the confessions and request for forgiveness, I addressed the gathering with the following Proclamation.

Representative Reconciliation Proclamation To the San Carlos Apache People

October 5, 1996

On April 30, 1871, a group of vigilantes out of Tucson treacherously attacked the peaceful, sleeping, Apache Camp. It is reported that of the 144 killed, most were defenseless women and children. Only eight were adult males. Eastern newspapers named this tragedy the “Camp Grant Massacre.” The nation was outraged, but only for a short time. One year later in Tucson, an unsympathetic court acquitted the perpetrators. The citizens of Arizona stood quiet. The lost and their families still suffer the injustice.

As citizens of Tucson, Arizona, on this day of October 5, 1996, we humbly take “Representative Responsibility” for these unthinkable acts, and beg your forgiveness for them as if they were our own.

We honor the San Carlos Apache people and vow to stand with you as brothers and sisters in times of adversity and peace.

We declare this to be the first day of the year of Jubilee and profess our intent to establish growing relationships with you. We pledge to learn to stand by your side as servants, helpers and friends.

We are determined to help raise a memorial as a remembrance to remind us to stand together as brothers and sisters regardless of what the future may hold.

We sign as representatives of Tucson and Arizona:

At the conclusion of the reading of the proclamation and presentation to Chairman Stanley and the Museum, Chairman Stanley responded, “As the elected Chairman of the San Carlos Apache Tribe, I grant Tucson forgiveness for the Camp Grant Massacre.” He then said, “I also beg your forgiveness for the many ways in which we violated you.”

David Miles stood before us and said in the midst of tears, “Now, I can look a white man in the eyes. . .” Dale Miles made a few similar comments and received the proclamation on behalf of the museum. We concluded the ceremony by providing a traditional Apache meal.

We have raised $600 for a bronze marker to be presented to the Tribal Chairman on April 30, 1998. It will be a copy of the proclamation. Currently we are negotiating with an artist to produce the marker.

Following that ceremony, many of us then proceeded to the actual site.

In Esperanza Means Hope, Carlos tells his sister the story that sparked war between Cochise and his Chokonen band of Chiricahuas and the U.S. government in 1861. The event is referred to as the Bascom Affair and is described on page 157 of the book. The event took place in the remote Apache Pass, near the site where Fort Bowie was built a year later. Some of the specifics of the event are disputed and accounts of the story vary because official Army records are missing.

The sequence of events were as follows:

Mickey Free

There are no known pictures of Cochise, but there are several written accounts of his appearance and character. Read through the following pages in Esperanza Means Hope to reacquaint yourself with Carlos’ view and description of meetings with Cochise: pages 146 -147; 158; 161- 163; and 172- 174.

Now read through a few other descriptions of Cochise. The first is from Tom Jeffords, a white friend of Cochise and the first Indian agent for Cochise and his people.

# 1 – “I found him to be a man of great natural ability, a splendid specimen of physical manhood, standing about six feet two, with the eye of an eagle. This was the commencement of my friendship with Cochise and although I was frequently compelled to guide troops against him and his band, it never interfered with our friendship. He respected me, and I respected him. He was a man who scorned a liar, was truthful in all things. His religion was truth and loyalty.”

The second description is from an Army doctor, Dr. Anderson Ellis, who observed a meeting between Cochise and General Granger. Cochise is 56 years old at the time and still appears to be physically fit.

# 2 – “While he was talking, we had a fine opportunity to study this most remarkable man…His height, five feet ten inches; in person lithe and wiry, every muscle being well-rounded and firm. A silver thread was now and then visible in his otherwise black hair, which he wore cut straight around his head about on a level with his chin. His countenance displayed great force. Cochise spoke through an interpreter. He spoke in his language to one of his warriors who also spoke Spanish. The warrior repeated the words in Spanish to a Spanish speaker in Gen. Granger’s contingent, who then translated them into English for the general.”

Cochise declared: “When I was young, I walked all over this country, east and west, and saw no other people than the Apaches. After many summers I walked again and found another race of people had come to take it.”

“How is it? Why is it that the Apaches wait to die, that they carry their lives on their fingernails? They roam over the hills and the plains and want the heavens to fall on them. The Apaches were once a great nation. They are now but a few, and because of this they want to die, — and so carry their lives on their fingernails.”

When General Gordon Granger asked Cochise to move to a reservation in New Mexico, he replied:

“Now that I am cool I have come with my hands open to you to live in peace with you. I speak straight and I do not wish to deceive or be deceived. I want a good, long, lasting peace. When God made the world he gave one part to the white man and one to the Apache. Why as it? Why did they come together? Now that I am to speak, the sun, the moon, the earth, the air, the waters, the birds and the beasts, even the unborn children shall rejoice at my words… I do not wish to hide anything from you or have you hide anything from me; I shall not lie to you; do not lie to me. I want to live in these mountains; I do not want to go to Tularosa. That is a long ways off. The flies in those mountains eat out the eyes of the horses. The bad spirits live there. I have drunk of these waters and they have cooled me. I do not want to leave here.”

The third description is from General Oliver O. Howard who met with Cochise for 10 days in 1872 to make a peace with Cochise. Howard wrote a children’s book about the famous Indian chiefs he had met on the frontier. This excerpt is from his book.

#3 – “We had just had our breakfast when the chief (Cochise) rode in. He wore a single robe of stout cotton cloth and a Mexican sombrero on his head with eagle feathers on it. …When he saw us, he sprang from his horse and threw his arms around Jeffords and embraced him twice, first on one side, and then on the other. When Jeffords told him who I was, he turned to me in a gentlemanly way, holding out his hand and saying: Buenos dias Señor. He greeted us all pleasantly…

I answered him plainly that the President had sent me to make peace with him. He replied: Nobody wants peace more than I do. I have killed ten white men for every Indian I have lost, but still the white men are no less, and my tribe keeps growing smaller and smaller, till it will disappear from the face of the earth if we do not have a good peace soon.”

The final description is from Assistant Surgeon Henry Turrill who served at Fort Craig.

#4 – “Cochise impressed me as a wonderfully strong man, of much endurance and accustomed to command and to expect instant and implicit obedience. He was the greatest Indian I ever met.”

Cochise died before his people lost their homelands with the closure of the short-lived Chiricahua Reservation; his band and other Chiricahua Indians were transferred to the San Carlos Apache Reservation. They did not do well on the barren, inhospitable land because they were mountain Apaches.

![]()

Read Sgt. Polk’s description of the closure of the Chiricahua Reservation in Esperanza Means Hope on pages 102 – 103. Do you think that Papá’s response to Sgt. Polk’s comments is a fair one? Why or why not? Are you surprised that an Anglo soldier would take this sympathetic point-of-view regarding the Chiricahua Indians? Why or why not?

In April 1861, the Civil War began in the United States. As a result, Arizona’s Army troops were sent to fight the war and forts in Arizona were abandoned and some even burned. This left American settlers with no protection against attacks by Apaches. This lack of protection, the canceling of the Butterfield Stage Mail service through southern Arizona by the U.S. government and the refusal of the U.S. government to make Arizona a separate territory from the New Mexico Territory left many citizens of Tucson with sour feelings toward the federal government.

At the same time, the recently formed Confederate states made a strategic decision to invade the Southwest and to claim it for the Confederacy. They wished to expand slavery to this region. Soon, Lt. Colonel John Baylor invaded the New Mexico Territory and defeated the Union Army at Fort Fillmore near Mesilla, New Mexico.

Then Baylor made himself Territorial Governor of the new Confederate Territory of Arizona; the border of the Arizona Territory was the 34° N parallel line on a south-north line.

Of course, this was a short-lived Confederate territory because the Confederates were defeated in their attempt to invade the Southwest by Colorado Volunteers in March 1862. However, because of the Confederate interest in Arizona and the rich mineral ores in the region, in 1863, the United States government created a separate and new Territory of Arizona divided on an east-west line at the 109° parallel. Both the Union and Confederate governments claimed the territories until the close of the war. (Some people in southern Arizona continued to support the Confederacy throughout the war.)

The Battle of Apache Pass was a two day-skirmish between California Volunteers fighting with the Union Army and the Chiricahua Apaches. A large force of California Volunteers marched across southern Arizona toward the New Mexico Territory to fight the invading Confederates. Unknown to them at the time, the Confederates had already been defeated.

However, General Carleton, the commander of the California Volunteers divided his large column of troops into smaller groups to set out across the hot and harsh desert in the summer of 1861. One group made it through Apache Pass without problems; a second force of 126 soldiers, 22 wagons and two howitzers arrived at Apache Pass on July 15th where Apaches awaited them and fighting began.

Civil War era howitzer

Eventually the Apaches were scattered by the firing of the howitzers. However, the Apaches held the water springs at Apache Pass. A five-hour battle ensued and the Apaches were eventually driven out of their positions and the California troopers held the springs. The next day, July 16th, the battle resumed, but for a brief time, due to the howitzers being fired again.

Because of the importance of the springs and the Apache Pass region, General Carleton authorized the building of a fort in the area. Some of the California volunteers set to work on the construction of the adobe structures that would become Fort Bowie.

1887 |

1898 |

1905 |

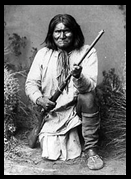

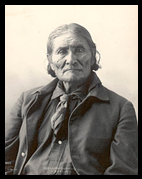

Geronimo’s Apache name was Goyahkla meaning, “one who yawns,” although there are conflicting interpretations about the meaning of the name. He was born (sometime in the 1820s) into the Bedonkohe band of Chiricahua Apaches. His adult life was greatly impacted by the murders of his mother, first wife, Alope, and three children at the hands of Mexican soldiers under General Carracsco at Janos, Mexico (1850).

In a battle of revenge at Arispe (1852), Sonora, Goyahkla earned his famous name, “Geronimo” for his furious, courageous and frenzied combat. He himself said of the battle to avenge his family’s death, “In all the battle I thought of my murdered mother, wife and babies, of my father’s grave and my vow of vengeance, and I fought with fury. Many fell by my hand and constantly I led the advance.” After this battle, all recognized Geronimo’s courage and leadership skills.

Important note: Geronimo was never a Chiricahua chief; he was a medicine man, a spiritual leader and a warrior. He did, however, become a legend, in his own lifetime, because of his steadfast resistance to the effort to remove him and his people from their homelands and to change their way of life. (Feelings about Geronimo are mixed, however. Some believe that ultimately, all Chiricahuas suffered as a result of Geronimo’s resistance, for they all lived out their lives as prisoners-of-war. They were not permitted to return to Arizona.)

In 1872, when Cochise made peace with the U.S. government and agreed to live on the Chiricahua Reservation, Geronimo also agreed to the peace. However, when in 1876, Indian Agent John Clum was ordered to bring the Chiricahuas to the San Carlos Reservation and close the Chiricahua Reservation, Geronimo escaped with about 400 other Chiricahuas.

In 1877, John Clum’s men captured and imprisoned Geronimo by a ruse (trick) and forced him to join other Chiricahuas on the overcrowded and dismal San Carlos Reservation. Clum boasted that he was the only one to ever capture Geronimo; Geronimo taunted Clum by pointing out that “shooting” was not involved in his capture.

He escaped again in 1878 and in 1881. His escapes alternated with returns to the San Carlos Reservation until his fourth and final escape and subsequent agreement to submit to the arrangements for his people made by the U.S. government.

In May 1885, a band of 144 Apaches, led by Geronimo and others, left the San Carlos reservation and fled to Mexico’s Sierra Madre Mountains. General George Crook pursued them for ten months unsuccessfully until he enlisted the help of Apache scouts.

In March, 1886, Geronimo agreed to surrender to Crook at Camp el Cañon de los Embudos, but, on the night before, changed his mind because he heard a rumor he was to be killed, and again took off across the border, leaving General Crook to explain his disappearance to his superiors.

Because he believed that General Sheridan and the President no longer supported his decisions, General Crook resigned his command (Department of Arizona) after Geronimo’s escape and was immediately replaced by the General Nelson A. Miles.

At this point, Geronimo’s group consisted of only 39 people, mostly family members. To track them down, 5000 U.S. soldiers, 3000 Mexican soldiers, and 500 scouts took up the pursuit; surprisingly, Geronimo’s party successfully evaded capture. At last, one of Geronimo’s group members left the stronghold and returned to the reservation. He led the Army back to Geronimo’s base.

In August 1886, Lieutenant Charles Gatewood met with Geronimo and persuaded him to meet with General Nelson Miles. After negotiating what he believed to be only a brief exile from his homelands, Geronimo agreed to General Miles’ surrender terms for the final time.

This meeting took place at Skeleton Canyon (near Douglas) in September 1886. From there, Geronimo’s band and all other Chiricauhuas – even those who had not resisted and were living peaceably at Turkey Creek – were escorted to Fort Bowie and later removed to Florida. A year later, the Chiricahuas were transferred to Alabama; many of them had died of malaria in Florida and now died of tuberculosis in Alabama. Only about 300 people – including Geronimo – were transferred to Oklahoma; for 27 years, they lived as prisoners-of-war.

Geronimo lived until 1909 at Fort Sill in Oklahoma, becoming a public figure and national celebrity in his old age. He rode in Theodore Roosevelt’s inaugural parade, attended the St. Louis World’s Fair and sold the buttons off of his jackets as souvenirs to the unsuspecting who didn’t realize that Geronimo had a stash of the buttons. He posed for photos and dictated an autobiography of his life. When he died he had $10,000 in a bank account.

Geronimo's Burial Site in Oklahoma

Sheridan |

Crook |

Miles |

Drum |

Reader A:

FR: Camp el Canon de los Embudos, 20 miles SE of San Bernardino, Mexico

– March 26, 1886

TO: Lieutenant-General P.H. Sheridan, Washington DC

I met the hostiles yesterday at Lieut. Maus’ camp, they being located about five hundred yards distant. I found them very independent, and fierce as so many tigers. Knowing what pitiless brutes they are themselves, they mistrust everyone else. After my talk with them it seemed as if it would be impossible to get any hold on them, except on condition that they be allowed to return to their reservation on their old status. Today things look more favorable.

George E. Crook, Brigadier General

Reader A:

FR: Camp el Canon de los Embudos, March 27, 1886

TO: Lieutenant-General P.H. Sheridan, Washington DC, Confidential

In conference with Geronimo and the other Chiricahuas I told them they must decide at once on unconditional surrender or to fight it out. That in the latter event hostilities should be resumed at once, and the last one of them killed if it took fifty years. I told them to reflect on what they would to do before giving me their answer. The only propositions they would entertain were these three: That they should be sent east for not exceeding two years, taking with them such of their families as so desired, leaving an Apache Nana who is seventy years old; or that they should all return to the reservation upon their old status; or else return to the war-path with its horrors.

As I had to act at once I have today accepted their surrender upon the first proposition. Kaetena, the young chief who less than two years ago was the worst Chiricahua of the whole lot, is now perfectly subdued. He is thoroughly reconstructed, has rendered me valuable assistance, and will be of great service in helping to control these Indians in the future. His stay at Alcatraz has worked a complete reformation in his character. I have not a doubt that similar treatment will produce same results with the whole band, and that by the end of that time the excitement here will have died away.

Mangus, with thirteen Chiricahuas, six of whom are bucks, is not with the other Chiricahuas. He separated from them in August last, and has since held no communication with them. He has committed no depredations. As it would be likely to take at least a year to find him in the immense ranges of mountains to the south, I think it inadvisable to attempt any search at this time, especially as he will undoubtedly give himself up as soon as he hears what the others have done.

I start for Bowie tomorrow morning, to reach there next night. I respectfully request to be informed whether or not my action has been approved, and also that full instructions meet me at that point. The Chiricahuas start for Bowie tomorrow with the Apache scouts under Lieutenant Maus.

George Crook, Brigadier General

Reader B:

FR: Washington DC, March 30, 1886

TO: General George Crook, Fort Bowie, Arizona

You are confidentially informed that your telegram of March 29th is received. The President cannot assent to the surrender of the hostiles on the terms that their imprisonment last for two years, with the understanding of their return to the reservation. He instructs you to enter into negotiations on the terms of their unconditional surrender, only sparing their lives; in the meantime, and on the receipt of this order, you are directed to take every precaution against the escape of the hostiles, which must not be allowed under any circumstances. You must make at once such disposition of your troops as will insure against further hostilities by completing the destruction of the hostiles unless these terms are accepted.

P.H. Sheridan, Lieut.-Gen.

Reader A:

FR: Fort Bowie, A.T., March 30, 1886

TO: Lieut.-Gen. P.H. Sheridan, Washington, DC

A courier just in from Lieut. Maus reports that during last night Geronimo and Natchez with twenty men and thirteen women left his camp, taking no stock. He states that there was no apparent cause for their leaving. Two dispatches received from him this morning reported everything going on well and the Chiricahuas in good spirits. Chihuahua and twelve men remained behind. Lieut. Maus with his scouts, except enough to take the other prisoners to Bowie, have gone in pursuit.

Geo. Crook, Brigadier-General

Reader B:

FR: Washington, DC, March 31, 1886

TO: General George Crook, Fort Bowie, A.T.

Your dispatch of yesterday received. It has occasioned great disappointment. It seems strange that Geronimo and party could have escaped without the knowledge of the scouts.

P.H. Sheridan, Lieut.-General

Reader A:

FR: Fort Bowie, A.T., March 31, 1886

TO: Lieut.-General P.H. Sheridan, Washington, DC

In reply to your dispatch of March thirtieth, to enable you to clearly understand the situation, it should be remembered that the hostiles had an agreement with Lieut. Maus that they were to be met by me twenty-five miles below the line, and that no regular troops were to be present. While I was adverse (very against) such an arrangement, I had to abide by it, as it had already been entered into. We found them in camp on a rocky hill about five hundred yards from Lieut. Maus, in such a position that a thousand men could not have surrounded them with any possibility of capturing them. They were able, upon the approach of any enemy being signaled, to scatter and escape through dozens of ravines and canons, which would shelter them from pursuit until they reached the higher ranges in the vicinity. They were armed to the teeth, having the most approved guns and all the ammunition they could carry. The clothing and other supplies lost in the fight with Crawford had been replaced by blankets and shirts obtained in Mexico. Lieut. Maus, with Apache scouts, was camped at the nearest point the hostiles would agree to their approaching.

Even had I been disposed to betray the confidence they placed in me, it would have been simply an impossibility to get white troops to that point either by day or by night without their knowledge, and had I attempted to do this the whole band would have stampeded back to the mountains. So suspicious were they that never more than from five to eight of the men came into our camp at one time, and to have attempted the arrest of those would have stampeded the others to the mountains. Even after the march to Bowie began we were compelled to allow them to scatter. They would not march in a body, and had any efforts been made to keep them together they would have broken for the mountains. My only hope was to get their confidence on the march through Kaetena and other confidential Indians, and finally to put them on the cars, and until this was done it was impossible to disarm them.

George Crook, Brigadier-General, Commanding

Reader B:

FR: Washington, DC, April 1, 1886

TO: General George Crook, Fort Bowie, A.T.

Your dispatch of March thirty-first received. I do not see what you can now do except to concentrate your troops at the best points and give protection to the people. Geronimo will undoubtedly enter upon other raids of murder and robbery, and as the offensive campaign against him with scouts has failed, would it not be best to take up the defensive and give protection to the people and business interests of Arizona and New Mexico. The infantry might be stationed by companies at certain points requiring protection, and the cavalry patrol between them. You have in your department forty-three companies of infantry and forty companies of cavalry, and ought to be able to do a good deal with such a force. Please send me a statement of what you contemplate for the future.

P.H. Sheridan, Lieut.-General

Reader A:

FR: Fort Bowie, A.T., April 1, 1886

TO: Lieut.-General P.H. Sheridan, DC

Your dispatch of today received. It has been my aim throughout present operations to afford the greatest amount of protection to life and property interests, and troops have been stationed accordingly. Troops cannot protect property beyond a radius of one-half mile from their camp. If offensive movements against the Indians are not resumed, they may remain quietly in the mountains for an indefinite time without crossing the line, and yet their very presence there will be a constant menace and require the department to be at all times in position to repress sudden raids, and so long as any remain out they will form a nucleus for disaffected Indians from the different agencies in Arizona and New Mexico to join. That the operations of the scouts in Mexico have not proven as successful as was hoped, is due to the enormous difficulties they have been compelled to encounter from the nature of the Indians they have been hunting, and the character of the country in which they have operated, and of which persons not thoroughly conversant with both can have no conception. I believe that the plan upon which I have conducted operations is the one most likely to prove successful in the end. It may be, however, that I am too much wedded to my own views in this matter, and as I have spent nearly eight years of the hardest work in my life in this department, I respectfully request that I may now be relieved from its command.

George Crook, Brigadier-General

Reader C:

FR: Washington, DC, April 2, 1886

TO: General N.A. Miles, Fort Leavenworth, Kansas

Orders of this day assign you to command the Department of Arizona to relieve General Crook. Instructions will be sent you.

R.C. Drum, Adjutant-General

Reader A:

FR: Fort Bowie, A.T., April 2, 1886

TO: Lieut.-General P.H. Sheridan, Washington, DC

The hostiles who did not leave with Geronimo arrived today. About eighty. I have not ascertained the exact number. Some of the worst of the band are among them. In my judgment they should be sent away at once, as the effect on those still out would be much better than to confine them. After they get to their destination, if they can be shown that their future will be better by remaining than to return, I think there will be but little difficulty in obtaining their consent to remain indefinitely. When sent off a guard should accompany them.

George Crook, Brigadier-General

Reader B:

FR: Washington, DC, April 2, 1886

TO: Gen. Geo. Crook, Fort Bowie, Ariz.

The present terms not having been agreed to here, and Geronimo having broken every condition of surrender, the Indians now in custody are to be held as prisoners and sent to Fort Marion without reference to previous communication and without, in any way, consulting their wishes in the matter. This is in addition to my previous telegram of today.

P. H. Sheridan, Lieut.-General

Reader C:

FR: Washington, DC, April 2, 1886

TO: General George Crook, Fort Bowie, A.T.

General Miles has been ordered to relieve you in command of the Department of Arizona and orders issued today. Advise General Miles where you will be.

R.C. Drum, Adjutant-General

Reader A:

FR: Fort Bowie, A.T., April 3, 1886

TO: General N.A. Miles, Fort Leavenworth, Kansas

Adjutant-General of the Army telegraphs that you have been directed to relieve me in command of Dept. of Arizona. Shall remain at Fort Bowie. When can I expect you here?

George Crook, Brigadier-General

Reader D:

FR: Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, April 3, 1886

TO: General George Crook, Fort Bowie, A.T.

The order was a perfect surprise to me. I do not expect to leave here for several days, possibly, one week.

N.A. Miles, Brigadier-General

Reader C:

FR: Headquarters of the Army, Washington, DC, April 3, 1886

TO: General Nelson A. Miles, Fort Leavenworth, Kansas

The Lieutenant-General directs that on assuming command of the Department of Arizona, you fix your headquarters temporarily at or near some point on the Southern Pacific RR.

He directs that the greatest care be taken to prevent the spread of hostilities among friendly Indians in your command, and that the most vigorous operations looking to the destruction or capture of the hostiles be ceaselessly carried on. He does not wish to embarrass you by undertaking at this distance to give specific instructions in relations to operations against the hostiles, but it is deemed advisable to suggest the necessity of making active and prominent use of the regular troops of your command. It is desired that you proceed to Arizona as soon as practicable.

R.C. Drum, Adjutant-General